- Home

- Neema Shah

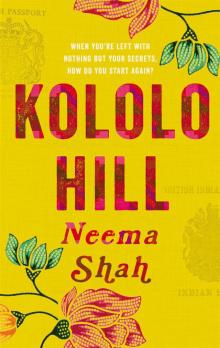

Kololo Hill Page 30

Kololo Hill Read online

Page 30

‘But you let it happen to December?’

She watched him, how small he seemed as he collapsed onto the bed.

‘All I ever wanted was no secrets,’ she said. ‘To stick together, no matter what.’

She lay down next to him, neither touching the other. What use were words now? She couldn’t change any of it. And leaving aside the past, what about all his obsessive plans to return, when all she was trying to do was build something from the remnants of their old life? Something that had been small, like a tiny crack in a windowpane, had grown between them, until it could all collapse into nothing.

Now what? It wasn’t as though they could divorce, no one did that, not amongst the people they’d grown up with. The shame would tear her parents apart; Jaya too, who’d been there for her when no one else had been.

But how could Asha ignore all the lies he’d told, move on, pretend that they were just another ordinary couple? If they acted as if everything was normal, wouldn’t she be a liar too?

37

Asha

Asha pinned her sari into place as best she could. Still so difficult, even after years of practice.

‘Hurry up, Asha. We’ll be late,’ Pran called from the bottom of the stairs.

Asha rushed across the bedroom, nearly sending her pile of library books tumbling off the table. She wrapped herself in a blue saal to keep the cool weather out, and joined Pran and Jaya in the car. The Ford Cortina spluttered into life. Pran borrowed it from time to time from one of his friends at the factory, who’d bought it for next to nothing. A fact they were reminded of every time they turned the engine on.

‘It worked straight away!’ said Pran.

‘That’s a first.’ Asha looked across at him.

‘It’s not so bad,’ said Jaya.

‘Exactly, it gets us where we need to go, right?’ Pran said, tapping his hand against the dashboard as though he was petting a horse.

‘Better than getting the bus, I suppose. I can’t stay too late anyway.’ She was meeting Sinead for a coffee and a catch-up tomorrow. Asha played with her sari chundri as they made their way down Bounds Green Road.

‘Isn’t that the sari I bought you?’ Pran glanced at the fuchsia-pink silk, the gold-beaded embroidery.

Asha nodded. ‘Just after we got married.’

Pran smiled. ‘I thought so. I haven’t seen you wear it before.’

‘Not had the chance until now.’

They arrived at the wedding venue, a mahogany-panelled school hall in Enfield, the smell of wood polish mingling with the smoky sandalwood scent of agarbatti. The couple had already had a separate civil ceremony a couple of days before. The school hall was cheap to hire and served as a venue for the Hindu ceremony. The wedding had already started and the guests sat in rows facing the stage. The mandwo stood proudly on top, four carved wooden pillars, decorated here and there with whatever red plastic flowers they’d managed to get their hands on. Beneath it, the maharaj took the bride and groom through the rituals, while close family, including the bride’s mother, Kamlaben, looked on. Asha watched as the couple under the mandwo gazed at each other and repeated the Sanskrit words after the maharaj. How beautiful the scene looked, how similar to her own wedding. And how different the new couple’s lives would be from hers and Pran’s.

As usual, the guests continued chattering, paying little attention to the wedding ceremony itself. ‘If God had wanted us to stay quiet during a Hindu wedding, he’d have made it an hour shorter!’ Motichand used to say. He would wriggle and fidget his way through. Asha watched Pran as he went to sit with some friends from temple.

After the ceremony, they took their place in the queue for food, the air filling with the sweet scent of basmati rice and the lemony tang of curry leaves. Young men stood behind the table serving buteta nu shaak, small pieces of potato glistening in the tomato sauce; puffed up rounds of golden-brown puri; sweet saffron-coloured pearls of bundhi, all piled up in the little compartments of the white plastic plates.

Jaya inspected it all. She’d helped Kamlaben the day before with the food preparation, and was now bossing the servers about as she went along the line, telling them to serve bigger portions and complaining that the shaak wasn’t hot enough.

‘Look, Asha,’ Jaya said, as they took their places along the trestle table. She gestured to Ramniklal and Hiraben, who were waving from the other end of the hall. They hurried over with their own plates of food, smiling all the way.

‘Jayaben, how nice it is to see you.’ Hiraben clutched Jaya’s hand. ‘And Asha, you look so well!’ Jaya had written to Hiraben but they hadn’t seen each other since their first few months in England.

Asha introduced Pran. Ramniklal and Hiraben shared their news, how they’d settled down in the Midlands. After both working at the local typewriter factory, they’d managed to secure a business loan and started a newsagent with a distant cousin of Ramniklal’s.

‘He wants it open seven days a week,’ Hiraben rolled her eyes.

‘We’d have holidays too,’ Ramniklal protested.

‘Five hours on a Sunday afternoon is not a holiday,’ Hiraben smiled.

But though they both looked a little tired, their faces were full of a hope Asha hadn’t seen at the barracks.

Asha told them about her new job, working in the housing office of the local council.

‘And Vijaybhai?’ said Hiraben, taking another spoonful of bundhi.

‘He is still off roaming the world,’ said Jaya, shaking her head in mock annoyance. ‘But he says he’ll be back soon, or at least that’s what his last postcard told me.’

‘Well, I hear you have plenty to keep you occupied, Jayaben, with your own little empire,’ said Ramniklal, smiling. Jaya must have told him how she’d teamed up with Kamlaben, cooking at events. Pran had shown her how to keep her own accounts and she even put some money aside in a bank account each month.

Though Jaya spoke shyly, the pride in her eyes was clear to see. ‘Oh, it’s just a little bit here and there, thoru thoru.’

Asha looked at each of them as Jaya made plans for them to go and visit the couple, agreeing to stay over for a few nights. To relax and laugh and talk, free from the worry of being homeless and unemployed, seemed ridiculously indulgent, even now. But Asha loved the warmth of it, an intense happiness that filled her up.

‘We heard a lot about you,’ said Ramniklal, turning to Pran.

‘Oh yes? Asha probably said I smoke too much?’ Pran grinned.

Ramniklal looked awkwardly at Asha. ‘No, sorry, I meant your Ba. She told us about you in her letters. Your difficulties getting into England.’

‘Oh, I see,’ said Pran, looking down at his plate.

‘And you’re going back to Uganda soon?’ said Ramniklal.

‘You’re very brave.’ Hiraben leant forward, resting her arm on the table.

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ said Pran. ‘Amin will be gone soon.’

‘And the army?’ Ramniklal’s voice betrayed his concern.

Pran shrugged. ‘It’s fine. They’re saying they want people to help them run the old dukans.’

‘And Ashaben, you’ll go too?’ said Hiraben. It was plain to see on their friends’ faces, that same confusion that Asha and Jaya had felt ever since Pran first brought up Uganda again.

She shook her head. ‘I’ll leave the hard work to Pran.’

‘For now, at least,’ said Pran, shifting in his seat. ‘I’m going back next week.’

‘I’ve tried to talk Pran out of it, but he insists. So stubborn,’ Jaya’s voice went quiet. ‘I will stay here with Asha and Vikash, who used to live with us, said he could come back for a few months to help with the bills. Anyway, Vijay will arrive back soon enough.’ As well as the postcards, Vijay had sent a few photographs taken on his old Pentax. Vast temples, Jaya and Motichand’s family huddled together and smiling; each image had a date and a handwritten note from him. Jaya had put them all on the mantelpiece, tears of happiness and sadn

ess in her eyes.

Later, the hall was cleared and the chairs moved to the edges of the room while the harmonium player and a tabla player set up.

‘There’s garba?’ Jaya put her hands together.

‘The bride loves dancing, apparently,’ Hiraben said.

Asha joined Jaya and Hiraben. ‘Too much for me,’ said Ramniklal, taking a seat.

Pran went and sat with his friends to watch. Women and a few men formed a large circle and began the familiar dance, slow at first: a clap, a click, a clap, saris sweeping across the floor, moving around the room to the beat of the tabla and the deep melodies of the harmonium. The music getting faster with each round, the heavy timbre of the drumbeat vibrating through Asha’s body.

She watched Jaya and Hiraben giggling as they left the line, their faces glistening with sweat, the music too fast for them. Asha carried on with the younger women, their faces gleeful, dizzier with each round, on and on, round and round, head spinning, hair coming loose from her bun, skin slick with moisture, willing herself on and on, round and round, until finally she stumbled out of the circle.

‘You stayed so long, Ashaben.’ Hiraben came over and nudged her. ‘These young girls can keep dancing forever, heh, Jayaben? Remember those days?’

Asha tried to catch her breath.

‘Here,’ said Jaya, handing her a cup of water.

She gulped it down in one. ‘I think I need some fresh air.’

Asha went outside round the back of the school, where hopscotch games had been chalked into the playground in pastel pinks and mint green. In the sky, sunset began to give way to night.

A shiver ran up her neck.

Pran was already standing outside smoking, leaning against the wall. He turned towards her.

‘I’ll come back later,’ she said, voice cool. No point in pretending now, there was no one else around. She turned back.

‘Wait, stay a moment,’ Pran called out.

She stopped, her back to him. ‘What for?’

‘To talk.’

‘We’ve had plenty of time to talk.’ She looked back at the past few weeks, how they’d gone over the same things again and again. In public, they pretended that nothing had changed because it was easier than dealing with Jaya’s questions and worry.

‘But I’m leaving soon,’ said Pran.

‘I know.’ Asha turned towards him as he held his cigarette in the air. The muffled sound of wedding songs drifted outside, people singing about leaving home, making new families, happy new lives.

‘I don’t want to leave things like this between us.’

‘It’s too late for that.’

‘You’ll still join me later, though? You have to.’

‘I have to?’

‘I mean, if you don’t, what will people say? What about Ba?’

‘What would Ba think about what you did?’ The breeze had picked up, rustling through the chiffon of her sari.

‘You promised you wouldn’t tell her.’

‘Don’t worry, I’m still keeping your secrets.’ Asha laughed bitterly. Jaya had been through enough. Telling her the truth would break her into little pieces. It was the one thing they could both agree on. ‘You go to your precious Uganda and leave her in peace. Leave us both in peace.’

‘Don’t talk like that, please. Don’t you care what people think?’

She shrugged her shoulders. ‘I’d rather deal with people saying things than go back to that hell.’

‘You’ll change your mind. We’ll get everything back. Just give me some time.’

‘Time to let you lie to me again? Or time waiting until you’re killed out there?’

He kicked the sole of his shoe against the wall, whispering, but his voice was full of fury. ‘Don’t talk like that. I’m trying to help us . . .’ He carried on talking but Asha was no longer listening. The words were the same wherever she was, Uganda, England. When it all came down to it, she didn’t believe him any more. A strange calm settled in her chest as she turned away.

‘Wait, Asha, wait. There’s one more thing I need to ask you. Please.’

She stopped as she reached for the handle of the exit door, not bothering to turn back towards him. ‘What?’

‘What if I stayed? What if I didn’t go to Uganda? If I stayed with you here. We’d be OK then, wouldn’t we?’

Her hand remained on the door handle, knuckles red from the cold. She didn’t turn back. Instead, she caught her reflection in the glass. She saw Pran behind her, eyes frantic, desperate as he called her name again. She looked beyond, to the people inside, to the flashes of colour, the sequins glinting like stars, everyone dancing and laughing together.

Asha pulled the door open and went inside.

Acknowledgements

Many people helped me to take this story from a vague idea in my mind to my debut novel.

A huge thank you to my agent, Jenny Savill, who understood exactly what I wanted to do with Kololo Hill and made my dream a reality. Thank you also to the Andrew Nurnberg Associates team who’ve championed this book throughout.

I’m indebted to the entire team at Picador; our first meeting felt like coming home. Your passion and dedication have shone through every step of the way. A special thank you to my brilliant editor, Ansa Khan Khattak, for your insightful comments and for sometimes knowing Jaya and her family better than I did. So many others have played a part in bringing Kololo Hill into the world, including Chloe May whose hard work has pushed Kololo Hill through the editing stages and into print, Lucy Scholes who has designed a dream cover that I’m so proud to show off and Emma Bravo, Katie Bowden and Kate Green who have all tirelessly spread the word about my book. Thank you all.

Debi Alper and Emma Darwin, you are superwomen. The ‘Self-Edit Your Novel’ course helped make Kololo Hill what it is today.

I thought that I was entering an ordinary writing competition in 2018, but how wrong I was about the Bath Novel Award. I’m honoured to be a part of your international community. Thank you to the BNA readers and, in particular, Caroline Ambrose, for helping me on my journey.

A huge thank you to Aki Schilz and Joe Sedgwick at The Literary Consultancy, Anjali Joseph at UEA, Spread the Word, Lorena Goldsmith and the DGA First Novel Prize, CBC Creative, Jericho Writers and the wonderful Andrew Wille. The ability to hear other authors’ success stories at the London Writers’ Cafe, Asian Writers’ Festival and Riff Raff London events inspired me to keep going.

I wouldn’t have written a word of this novel if it hadn’t been for Deborah Andrew’s early support. You pushed me to take risks and gave me the tools to write no matter what. Thank you for helping me to fall in love with writing again after twenty years away from the page.

The goodwill of the entire writing community is extraordinary, but I could never have dreamt of meeting friends like the #VWG. Your talents inspired me and your kindness nourished me when I needed it most, as well as keeping me entertained when I really should have been working on my book!

A number of early readers provided excellent feedback. Daniel Aubrey, whose enthusiastic support, talent for writing page-turners and selecting funny GIFs knows no bounds; and Lorna (Loarn) Paterson, kind, tireless and meticulous. You both cheered me on and showed endless patience while reading my many drafts. Thanks also to Sheena Meredith, Cathy Parmenter and Gill Perdue for taking the time to read later versions.

Thanks to my beautiful friends Finn, Hema, Lisa and Marina, who made me smile, celebrated my successes and kept me going through everything.

Finally, my love and thanks to my parents and grandparents, who made sacrifices in their lives so that I could have a world of opportunity in my own.

Author’s Note

It’s always interesting, explaining my family background. ‘I’m British Asian, but my parents are East African Asians, my ancestors are from India.’ Cue various explanations of how that came to be. My mum was born in Kenya, my dad in Tanzania, and I spent many family holidays enjoying the places whe

re they’d grown up.

There was also a wider story, one that very few British people appeared to know about, unless they recalled the news reports from the early 1970s. The story of 80,000 Ugandan Asians expelled from their home. I’d often wondered what it would be like to leave everything you know and love behind, to start again. When children at school told me to ‘go back to my own country’, I spent a lot of time wondering where my ‘own country’ was. I would think hard about what my family would do, where they would go, and decades later I finally had the opportunity to explore those questions through my writing. This novel is inspired by real-life events. I have tried to be as authentic as possible in bringing that history to life, but Kololo Hill is, of course, primarily a work of fiction. The characters in the book are not based on anyone in particular but were partly inspired by the many accounts I read during my research, as well as various people in my own family who left their homes and found countless ways to not only survive, but build successful new lives.

I used a variety of resources to research the Ugandan Asian experience. Yasmin Alibhai-Brown’s wonderful The Settler’s Cookbook: A Memoir of Love, Migration and Food gave me a window into colonial East Africa and a first-hand account of what it’s like to grow up as an Asian in Uganda; her descriptions of the culture, experiences and history of the time helped me to bring certain moments to life.

Immigrants Settling in the City: Ugandan Asians in Leicester by Valerie Barrett and From Citizen to Refugee: Uganda Asians Come to Britain by Mahmood Mamdani enabled me to understand what it must have been like for those trying to rebuild their lives in a new country. Hansard (Hansard.parliament.uk) helped me piece together the British government’s response to Idi Amin’s decree and the subsequent treatment of the refugees.

‘Exiles: Ugandan Asians in the UK’, an oral history project by the SOAS Centre for Migration and Diaspora Studies in collaboration with the Royal Commonwealth Society and the Council of Asian People (CAP), provided me with rare first-hand accounts of the Ugandan Asian expulsion. The BBC website and YouTube both gave me access to lots of archive material from the early 1970s, in both East Africa and Britain.

Kololo Hill

Kololo Hill